Living on $1 Day

This past weekend, I volunteered at a clinic in Puerto Peñasco, Mexico (better known to Americans as “Rocky Point”). The clinic was makeshift, conducted in a church in a local neighborhood. It was completely free to the residents and funded with donations.

The surrounding residents would be considered low income by American standards, but I sat on many pre-visit interviews with them and most of them don’t think of themselves as struggling. They’re really just living their lives.

The locals have differences in their lives that I simply haven’t experienced. In my makeshift Spanish, I learned that one woman, Guadalupe, had been waiting at the free clinic for about 8 hours, not knowing when she would be seen.

One of the nurses who didn’t speak Spanish was trying to communicate with her, none of the official translators was available, and so I was the stand-in. My Spanish is mediocre at best, but I can usually communicate with someone, albeit a little slowly.

After going back and forth between the doctors and Lupe, I had gotten her higher up on the list but couldn’t really promise much. I felt bad. I had become her “representative” for the clinic, but I couldn’t offer her anything tangible beyond “we’re working on it as fast as we can.”

“Lo siento, Guadalupe. Muchas gracias para esperar…” I said. I’m sorry, Guadalupe. Thank you so much for waiting…

“No, gracias a ustedes,” she said. “Lo agradezco tanto que me ayudan.” No, thank you to all of you. I so appreciate your help.

Another woman waited all day as well, and in her exit interview, when asked if she minded the wait, she smiled and said it hardly mattered compared to a doctor spending an hour with her.

So what does all of this have to do with the title of this post, $1/day? I actually think the residents of Puerto Peñasco earn significantly more than that. But when we got home tonight, I decided to watch the wonderfully done documentary Living on One Dollar on Netflix.

It’s about four American college students who go to Guatemala for 60 days, give themselves an income equivalent to the local population (roughly a dollar per day), and see what it’s like to live in extreme poverty.

In the movie, they live in the small town of Peña Blanca, where they experience such great generosity from people who have so little, and discover that small, incremental changes make all the difference at that level.

There were two interesting parallels I saw between the residents of Puerto Peñasco and those of Peña Blanca. First, in both cases, the natural temptation as a “wealthy” American is to pity the community, and to dwell on how many hardships they have. But when you actually get into the community, you discover people who do not sit around feeling bad for themselves. Instead, they have hopes, dreams, and desires like all of us, and they just want to get on with their lives.

I like how my wife put it. To pity them is to disrespect them. Instead, if we’re there to help out, just focus on how we might be able to solve any problems they may be having.

Second, I saw such intelligence and such a warm spirit in both communities. Not one patient in the clinic complained, even those with serious maladies, sometimes multiple conditions at once. And likewise in the village of Peña Blanca, the documentary displays a strong sense of community and a beautiful spirit of compassion among the locals.

It made me think about the relative economics of it all. The reality is that, in the case of Peña Blanca, I’ll earn more money in a single month than they will earn in 15 years. It’s a nearly 200-to-1 earnings ratio. Financially, there’s no contest.

That feels unfair. Out of that 200-to-1 ratio, how much of the 200 is due to any talents I might have versus simply the environment into which I was born, and the society in which I live, or even the “evolutionary paradigm” (more on that in a moment) in which I exist? In other words, how much of that is just because of luck?

I may understand the economic forces that give rise to that disparity, but how much did I do personally to be at the favorable end of them?

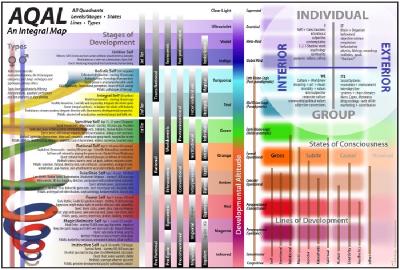

And then there’s this somewhat complicated looking diagram. You can click the image to see the full view, or just keep reading:

This diagram shows “Spiral Dynamics,” a concept I first learned about while reading a speech from Whole Foods CEO John Mackey. The basic idea here is that, as a society and as individuals we operate within the context of an “evolutionary paradigm.” We’ve already come a long way from the days of “survival bands”, authoritarian nation states, or feudalism, but we still have further to go.

The interesting thing is that, for each phase, different skills serve us. For example, during the “Early Mythic, Feudal, and Exploitive Empire” phase, being politically savvy was far more valuable (in the eyes of society, at least) than being a talented analytical engineer. Today’s society happens to reward skills that are in high demand and short supply. But Spiral Dynamics also imagines a world where the concept of “short supply” mostly doesn’t exist, and we live in such universal abundance that our pursuits are focused primarily on self-betterment and “peace in an incomprehensible world.”

My main point here is that the same person who might be thought of as a major success in 2015 may fare differently — better or worse — in a society that lives under a different evolutionary paradigm. And vice versa.

Anyway, it all says to me to be grateful for the successes we’ve experienced in our lives, humbled by all the forces way outside our control that conspired to help us achieve those successes, and compassionate toward our fellow humans.

Heady post, but thanks for reading!

Comments

comments powered by Disqus